On any given weekday, commuters in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, are snarled in traffic for hours.

Container trucks and tankers take up several lanes of traffic on the major thoroughfares close to the city’s ports. Often these trucks have been parked on the highways overnight.

Cars and minivans snake along the remaining single lane, sharing it with pedestrians fighting off early-morning road rage as they slowly make their way from one end of the city to another. There is a palpable fear of accidents, or a spill. Much of Lagos is an environmental disaster waiting to happen.

It is here in this vibrant metropolis of 21 million people that Africa’s richest person, Aliko Dangote, is undertaking his most audacious gamble yet. Mr. Dangote is building a $12 billion oil refinery on 6,180 acres of swampland that, if successful,— could transform Nigeria’s corrupt and underperforming petroleum industry. It is an entrenched system that some say has contributed to millions languishing in poverty and bled the “giant of Africa’’ for decades.

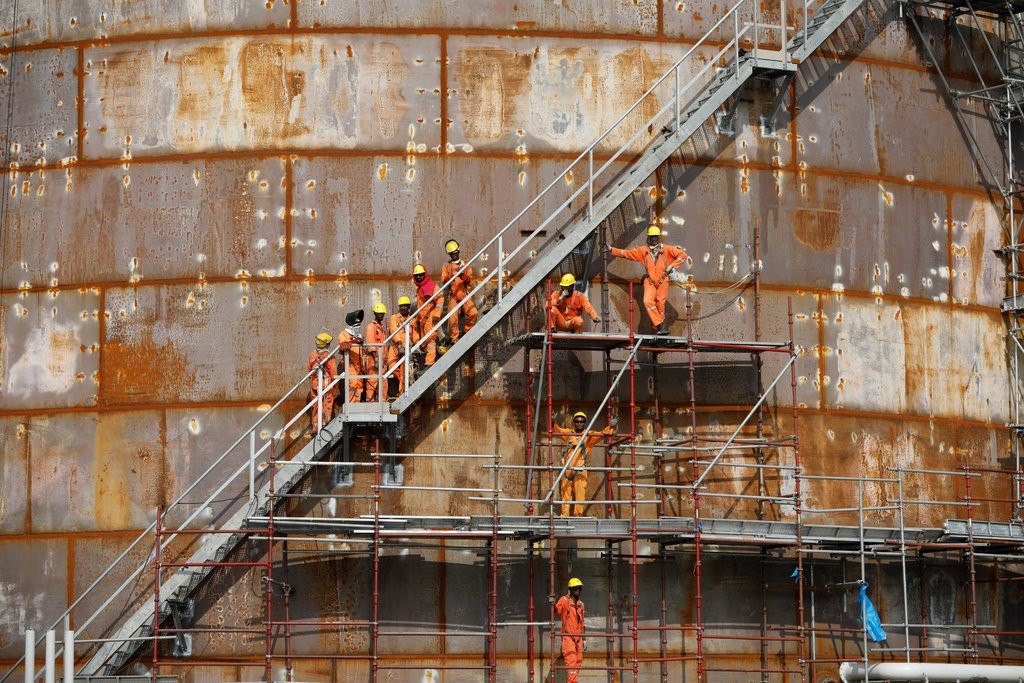

Planned as the world’s largest refinery, Mr. Dangote’s project is set in a free-trade zone between the Atlantic Ocean and the Lekki Lagoon, an hour outside the city center. The site employs thousands, and upon completion — Mr. Dangote says in 2020; some analysts suggest more likely in 2022 — should process 650,000 barrels of crude oil daily.

That’s enough oil to supply gasoline and kerosene to all 190 million Nigerians and still have plenty to export. By the end of this year, the facility is expected to churn out three million tons of fertilizer. The production of diesel, aviation fuel and plastics will then follow.

“The construction site is already a huge beehive of activities, with workers, local and foreign, hard at work. It is going to be the largest manufacturing plant of any sort in Lagos,” said Kayode Ogunbunmi, the publisher of City Voice, a Lagos daily newspaper and lifelong Lagos resident.

Indeed, some 7,000 employees are working around the clock on the site, many arriving by private ferry from the city center. Another 900 Nigerian engineers and technicians are being trained abroad for jobs at the refinery. Mr. Dangote, whose net worth is estimated at $11.2 billion, has had to build a port, jetty and roads to accommodate this project, along with new energy plants to power it all.

Nigeria’s government, despite being a longtime crude oil exporter, has four underperforming and frequently broken down refineries with a combined capacity of 445,000 barrels daily. Those refineries — two in the oil hub of Port Harcourt, one in Warri in the Niger Delta, and the other in the northern city of Kaduna — are all operating at less than 50 percent of capacity.

Which means that even though Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil producer, petroleum for everyday use must be imported. This has spawned fuel importers and diesel traders who have grown extremely wealthy. Nigeria’s government subsidizes fuel imports to keep pump prices low, and this has contributed to Nigeria’s well-documented culture of petroleum industry corruption.

“The failure to produce refined products over the last 25 years has created a huge architecture of graft and corruption around everything,” said Antony Goldman, the co-founder of the London-based Nigeria specialists ProMedia Consulting.

Mr. Goldman does political risk analysis in West Africa and has been working in and out of Nigeria for two decades. Corruption, he explained, stems from illegal refineries and the local criminal network that helps transport illegal crude out of the country. Both elements, he said, have not been sufficiently challenged by the government or law enforcement agencies, which has further contributed to Nigeria’s entrenched oil industry corruption.

“A refinery that actually works and can meet Nigeria’s refined product requirement? It’s a game changer,” Mr. Goldman added. But change, no matter how positive, is potentially destabilizing. “These are not people who relinquish things without a fight,” Mr. Goldman said of Nigeria’s fuel import merchants.

When Mr. Dangote initially unveiled his refinery plans in 2016, he said its aim was to challenge the status quo, which had seen the government spend about $5.8 billion to import petroleum products over the past year.

“This refinery is attacking the entire system,” he said. “You export jobs and create poverty here, so that’s what we are stopping,” he told reporters at the time.

Despite creating thousands of jobs, Mr. Dangote’s refinery hasn’t been universally applauded in Nigeria. The biggest issue is its Lagos location: The refinery is being built hundreds of miles from the impoverished Niger Delta, where the bulk of Nigeria’s oil is extracted.

Two undersea pipelines are under construction in the Delta and will carry petroleum about 340 miles to the refinery in Lagos.

The pipelines will be costly; but also far harder to sabotage than conventional aboveground systems. And security is key in the Delta region, where local rebel groups like the Delta Avengers have kidnapped foreign oil workers and blown up pipelines to protest regional pollution and poverty.

Amid Nigeria’s complex regional tensions, Mr. Dangote — a northerner by birth and Lagosian by decades of residence — is the one person, industry experts say, who could achieve a measure of détente in the region.

Yet critics — and Mr. Dangote has many — worry that his new refinery will allow him to essentially take over the Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. Why would a nation leave an entire industry in the hands of one company? they ask.

The “monopoly” question has swirled around Mr. Dangote for decades. Twice divorced and currently (and vocally) looking for a third wife, Mr. Dangote made his initial fortune operating near-monopolies in cement, flour and commodities across Nigeria, where regulatory oversight is relatively lax. Mr. Dangote’s companies, including pasta producers and property management, are found across Africa.

A decade ago, Mr. Dangote and other private investors tried and failed to buy the government-owned refineries. He was unavailable for comment, but previously told Reuters he does not apologize for his expansionist desires. “If you don’t have ambition,” he said, “you shouldn’t be alive.”

And for some in a tough business environment like Nigeria, a well-run monopoly is better than the current situation, where getting fuel remains an uncertainty. Indeed, despite oligarchy concerns, Mr. Goldman says he believes that Mr. Dangote’s past success actually bodes well for the refinery and Nigeria. “He has a record of success and delivery, and he doesn’t make mistakes on things like this,” Mr. Goldman said.

And Nigerians are tired of power cuts and overpriced gasoline.

“Most Nigerians see Aliko as a doer,” Mr. Ogunbunmi, the publisher, said. “Many quietly hope the refinery will help reduce uncertainties. Gasoline will be available, and possibly power.”

Beyond solidifying his own legacy, Mr. Dangote hopes his refinery will help diversify Nigeria’s economy while reducing its dependence on imported oil.

“We have other opportunities,” he said at the plant’s unveiling. “Agriculture is there. Petrochemicals are there, Nigeria has more arable land than China. If we finish our gas pipeline, it can generate 12,000 megahertz of power. That’s huge. That’s more than what we are looking for in Nigeria and we can supply the rest of West Africa.”

As his refinery nears completion, Mr. Dangote says he will soon focus on his next dream, owning Britain’s Arsenal football team. “Once I have finished with that headache, I will take on football,” he said. “I love Arsenal, and I will definitely go for it.”

______________________

Culled from the New York Times.

Edozien is the author of the book “Lives of Great Men,” a 2018 Lambda Literary Award winner and is director of the Reporting Africa program at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute.

Leave a Reply