This article was written by Paul Wallace. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

Nigeria’s central bank may soon give bond and stock investors what they have been pleading for: a weaker naira.

Governor Godwin Emefiele announced after a meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee in Abuja, the capital, on Tuesday that a more flexible foreign-exchange system would be unveiled “in the coming days.” But his statement was short on details and left plenty of questions. Here are some answers:

What’s the problem?

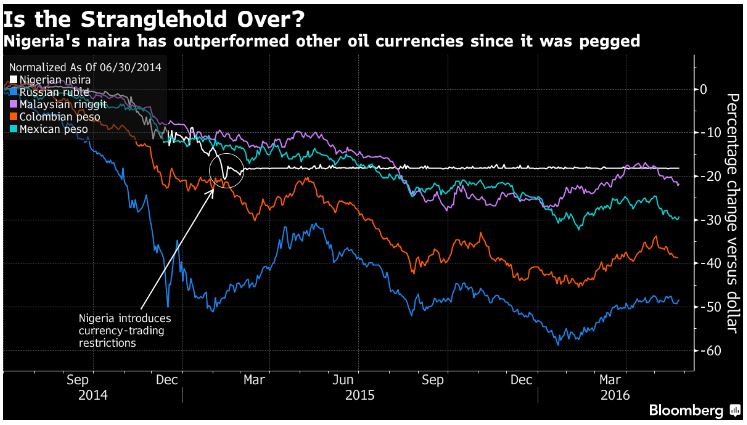

Nigeria has held the naira at 197-199 per dollar since March 2015, even as other oil exporters from Russia to Colombia and Malaysia let their currencies drop amid the slump in crude prices since mid-2014. Foreign reserves dwindled as the central bank defended the peg, while foreign investors, fearing a devaluation, sold Nigerian stocks and bonds.

While President Muhammadu Buhari and Emefiele argued a devaluation would fuel inflation, that happened anyway. Consumer prices accelerated at the fastest pace in six years in April as the black-market naira rate plummeted to about 350 against the dollar. To make matters worse, data released four days before the MPC meeting showed the economy contracted in the first quarter for the first time since 2004 as the dollar shortage curtailed manufacturing. That probably surprised policy makers, prompting the change of heart, according to Mathias Althoff, a fund manager in Stockholm at Tundra Fonder AB, which has about $200 million invested in frontier market stocks, including Nigerian banks.

What happens next?

While Emefiele didn’t specify what he meant by “greater flexibility,” analysts at Renaissance Capital Ltd. predict the central bank will allocate dollars at a fixed rate to strategic industries, such as energy and agriculture, while letting the naira weaken in the interbank market, where everyone else would buy their foreign currency. The central bank may also try try to control the new interbank rate by imposing a trading band of about 5 or 10 percent around it, according to Althoff.

Will that satisfy investors and save the economy?

If the central bank doesn’t allow the naira to drop enough, foreign investors will continue to shun Nigerian assets, according to Althoff. The currency should trade at around 285-290 per dollar, according to Alan Cameron, an economist at Exotix Partners LLP in London. A devaluation won’t solve Nigeria’s structural economic problems, which include an over-reliance on oil exports, and may fuel inflation in the short term. But it would make Nigerian exports more competitive, curb imports and encourage foreign investment.

What are the pitfalls?

Most investors would prefer a fully-floating naira, yet doubt that Nigeria, which has always had currency controls of some sort, will choose that option. And there are concerns it will be impossible for the central bank to ensure that only importers meeting its criteria are able to buy foreign currency at the discounted official rate. Many analysts fear that in a nation U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron described as “fantastically corrupt,” access to the official rate will come down to political connections.

“The suggestion of a dual exchange rate, with the maintenance of the official window, is a concern,” said Razia Khan, head of African research at Standard Chartered Plc in London. “This might lead to continued distortions in the market, ultimately with pressure on foreign-exchange reserves.”

What else should investors watch out for?

Buhari. He has made it clear that he, not Emefiele, is the person in charge of exchange-rate policy. The president is loath to allow the currency to drop unless he’s forced to and in February likened such a move to “murder.” He has yet to make any response to the MPC’s announcement. And while he is due to make a speech on May 29, the first anniversary of his coming to power, local press reports suggest he will focus on the government’s fight against corruption and Boko Haram’s Islamist insurgency.

The central bank has hinted at change before, only to do nothing. “The MPC has dangled the carrot of exchange-rate reform, but without giving any details of what a reformed market would look like,” said Cameron at Exotix. “To the skeptics among us, this will simply sound like a re-hash of the same old material we’ve been hearing about since December 2015.”

Leave a Reply